Throughout 1905 and 1906, the American magazine Collier’s published a series of articles by journalist Samuel A. Hopkins exposing the “fraud and poison” of the American pharmaceutical industry. One practice that drew Adams’ particular ire was the manufacture and sale of patent medicines–that is, medicines sold under brand names that were freely available without the need to obtain a prescription. At the time, there was no legislation at the federal level that regulated the advertising for these medicines, and misleading or outright false claims were very common. Additionally, manufacturers were free to put intoxicants and adulterants into their medicines with no obligation to make the formula public. Hopkins argued that these medicines–often advertised to mothers of young children–were creating addicts at an early age and resulted in disastrous effects to the consumers’ health.

Hopkins’ articles, later compiled as a book titled The Great American Fraud, were written at a time when political agitation for safer food and drugs was reaching its zenith. In the late 19th and early 20th century a variety of political movements made regulatory legislation a political goal, including the Progressive movement, the women’s suffrage movement, and the Temperance movement. These groups found a friend in Harvey W. Wiley, the chief chemist of the USDA and later the head of the Bureau of Chemistry. Partially due to Wiley’s efforts, several bills which would regulate food quality were introduced between 1880 and 1905, but none would pass both the House and the Senate. In the meantime, Wiley would raise awareness of the dangers of food adulterants by running government-funded medical trials where volunteers consumed chemicals such as formaldehyde and borax. These experiments–much like Hopkins’ writings–quickly became a cultural sensation.

Physicians and pharmacists were generally in favor of stricter regulation. Several major medical publications such as the Journal of the American Medical Association and American Medicine published articles warning doctors against patent medicines and would express support for legislation. Additionally, some food companies such as H. J. Heinz and many smaller businesses supported the implementation of quality standards. This may seem paradoxical, but increased regulation came with noticeable benefits for businesses: healthier workers, increased consumer confidence, and a consistent set of rules which held across state lines could all result in increased profits and lower operating costs. Of course, not every business stood to gain from increased regulation. Patent medicine manufacturers lobbied hard to kill any proposed legislation, often with great success.

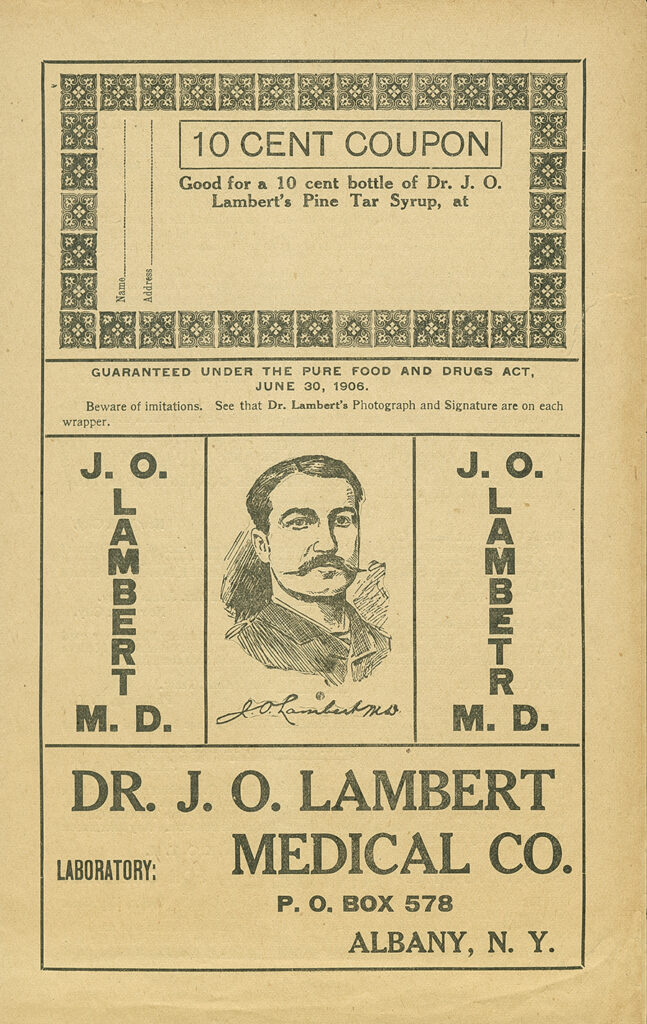

In 1906, the support for quality standards gained enough momentum to result in the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act. However, the scope of the Pure Food and Drug Act was quite limited. For the most part, the act regulated how manufacturers advertised their products rather than how they manufactured them. Producers were required to disclose any adulterants, preservatives, or narcotics they put into their products but there was no federal legislation actually preventing them from using them. The principal mechanism of enforcement was the seizure of mislabelled substances and prosecution of manufacturers. Although a significant amount of this enforcement was directed against the patent medicine industry, the prosecution had little effect as a deterrent since claims of fraud were often difficult to prosecute. These shortcomings would pave the way for more detailed legislation in subsequent decades.

This Dose of History was brought to you by AIHP Intern, Leo Ryan.

Bibliography:

Hopkins, Samuel Adams. The Great American Fraud. New York: Collier’s, 1906. https://archive.org/details/greatamericanfra00adam.

Fee, Elizabeth. “Samuel Adams Hopkins (1871-1958): Journalist and Muckraker.” American Journal of Public Health 100, no. 8 (2010): 1390-1391. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2901284/#bib2.

Valuck, Robert J., Suzanne Poirier, and Robert G. Mrtek. “Patent Medicine Muckraking: Influences on American Pharmacy, Social Reform, and Foreign Authors.” Pharmacy in History 34, no. 4 (1992): 183–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41111483.

Young, James Harvey. “Two Hoosiers and the Two Food Laws of 1906.” Indiana Magazine of History 88, no. 4 (1992): 303–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27791608.

Law, Marc T. “How Do Regulators Regulate? Enforcement of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, 1907-38.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 22, no. 2 (2006): 459–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4152843.

Wood, Donna J. “The Strategic Use of Public Policy: Business Support for the 1906 Food and Drug Act.” The Business History Review 59, no. 3 (1985): 403–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3114005.